Coop média de Montréal

Journalisme indépendant

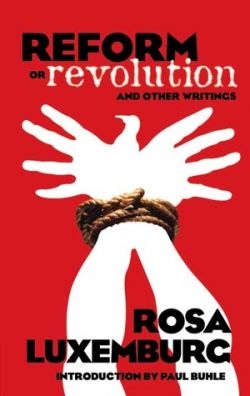

Québec Strike: Reform or Revolution

The Québec election raises important questions about the relationship between electoral and radical politics. Rosa Luxemburg’s “Reform or Revolution” is still one of the best texts I have read on this topic, and the piece does speak to our circumstances today. I hope this does spark some debate.

Divisions within the radical left fall along fairly conventional lines. Many argue that voting legitimizes an inherently illegitimate system. Chomsky said it best: “unfortunately, you can’t vote the rascals out, because you never voted them in, in the first place.” Others argue that electoral and parliamentary democracy can improve immediate social and living conditions through reform, effectively widen the cage or slackening the chain, as it were.

But as Luxemburg made clear, it makes little sense to counterpose reformism with the revolutionary intent of overthrowing capitalism. Luxemburg asks, “can we contrapose the social revolution, the transformation of the existing order, our final goal, to social reforms? Certainly not.”

Luxemburg guards strongly against reform as an end in itself. She writes in a lengthy but important passage that “people who pronounce themselves in favour of the method of legislative reform in place and in contradistinction to the conquest of political power and social revolution, do not really choose a more tranquil, calmer and slower road to the same goal, but a different goal.”

The Québec student strike of 2012 serves as a good example. After a sustained student strike produced a stalemate between the Liberal Party and the movement, the Liberals called an election. The Liberals claimed this would allow the “silent majority” to express their views on the strike.

The Fédération étudiante universitaire du Québec (FEUQ), one of the large student federations in Québec, opted for reformism early in the electoral campaign, shifting its attention away from enforcing strike mandates toward electioneering against the Liberals. Léo Bureau-Blouin, the former president of FECQ, became a candidate of the opposition Parti Québécois (PQ) and likewise said, “I’m not looking for global revolution. I’m trying to deal with these central social issues.”

This stands in stark contrast with the “combative syndicalism” of the Coalition large de l’Association pour une solidarité syndicale étudiante (CLASSE), a large student coalition which spearheaded the strike and continued to defy regressive anti-strike legislation after the election was called. The vision and strategy of CLASSE and FEUQ are radically different. As Luxembourg makes clear:

“Instead of taking a stand for the establishment of a new society they take a stand for surface modifications of the old society. […] Our program becomes not the realisation of socialism, but the reform of capitalism; not the suppression of the wage labour system but the diminution of exploitation, that is, the suppression of the abuses of capitalism instead of suppression of capitalism itself.”

The Québec election visibly pitted two systems of power against one another. There was the power of electoral democracy, with its figures campaigning for votes in the media and on the streets. And there is direct democracy, which, in my view, is far more in line with the basic principles of democracy. Candidates are campaigning for votes in the former. Various constituent groups are identified and messages are tailored to suit their interests. They are not meant to be active participants in the process, unless they can increase votes for a candidate or party.

One would be hard-pressed to say that constituents’ interests are represented once a candidate is elected. Elected members must follow the party line, and deviating from party doctrine to uphold constituent-interests would invite immediate party reprisal. In short, it would be hard to call our current form of parliamentary democracy truly representative.

What about the question of non-participation in electoral politics on the basis of principle? Some anarchists, for example, oppose all forms of state organization as a matter of principle. There is also a tendency within segments of the radical left to debase electoral politics. Participating in election campaign activity or working alongside a party is not well-respected relative to grassroots organizing. These activities are to be conducted with a degree of humility, if they are done at all. I find the perspective interesting and refreshing. It offers an important alternative to existing structures of power.

Two important questions here are if one is to engage in electoral democracy and parliamentary politics, to what end? And if one is to refrain from electoral politics, on what basis? It seems to me that if one is to participate in electoral politics, in should be part of a revolutionary movement built from the grassroots. Marx and Engels made this very clear in their circular letter of 1879 in stating that “the emancipation of the working class must be achieved by the working class itself. Hence we cannot co-operate with men who say openly that the workers are too uneducated to emancipate themselves, and must first be emancipated from above by philanthropic members of the upper and lower middle classes.” They were openly criticising the reformist tendencies of Eduard Bernstein and the Social Democratic Party (SDP).

Yet some anti-electoral anarchists make compelling arguments for abstention and against participation in electoral politics. The SDP itself did become reformist, hierarchical and bureaucratic. Of equal importance, devoting energies to electoral politics does drain energy and resources from directed democracy and action. There is also something to be said about assuming power within existing institutions: storm and pillage the castle, but the same walls still remain.

A common view is to argue that electoral and street-politics are equally important. I would agree, with the caveat that the long-term perspective is critical. I see no reason to fight for reform as an end in itself. Alleviating immediate concerns with a long-term perspective of radical change is a more promising route. The student strike in Québec offers hopeful signs of how this is to be done.

About the poster

Matthew Brett (Matthew Brett)

Montreal, Quebec

Member since May 2011

About:

Matt Brett is an anarchist, activist, writer and assistant publisher at Canadian Dimension magazine.Comments

Radical ideas alienate you

People are hesitant to stand on the side of revolution because that's radical and puts you outside of the mainstream. Being outside of the mainstream is scary for most of us. Unless there are strong leaders, like Hugo Chavez, who lead the way, ordinary people would feel like they are walking into the wilderness with these radical ideas.

The site for the Montreal local of The Media Co-op has been archived and will no longer be updated. Please visit the main Media Co-op website to learn more about the organization.