Coop média de Montréal

Journalisme indépendant

Exile & Austerity, Montreal, Night 86

A [Paul] Klee painting named Angelus Novus shows an angel looking as though he is about to move away from something he is fixedly contemplating. His eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.

-- Walter Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History” (1940)

One must have a home in order not to need it.

-- Jean Améry, "How Much Home Does a Person Need?" (1966)

* * *

I've been thinking a lot lately of home, history, and exile, and the intertwining legacies between them. Of the wreckage.

I'm in voluntary exile this summer. In so many small ways, though, my exile can be traced to my own brokenness, a "personal" narrative that is also constructed by the contemporary social conditions, which in turn are shaped by the "catastrophe" of history. Thus I experience a twist on another Améry essay, "The Necessity and Impossibility of Being a Jew": the necessity and impossibility of being at home in this world.

His essay speaks volumes to me, a godless Jew, in the wreckage of the Holocaust (which Améry survived and didn't survive) and the state of Israel. As an assimilated Jew prior to the Shoah, Améry had no relationship to Judaism and didn't identify with being Jewish; with the onset of National Socialism, he couldn't avoid being Jewish, or rather, it picked him out, tortured him, and put him in a concentration camp; after the Holocaust, he conjectures, it's both necessary to embrace our histories and impossible to do so. "With Jews as Jews I share practically nothing: no language and no cultural tradition . . . for me, being a Jew means feeling the tragedy of yesterday as an inner oppression. On my left forearm I bear the Auschwitz number; it reads more briefly than . . . the Talmud and yet provides more thorough information." Hence his further query, in another essay in his collection At the Mind's Limits, "How much home does a person need?" after he and millions of othered Others -- Jews, Roma, queers, those considered mentally or physically impaired, and more -- were forcibly exiled, and if not annihilated physically, then annihilated culturally, emotionally, materially. Their communities and worlds, often even a memory of them, were forever gone.

This necessity-impossibility paradox seems to mark the human condition at this juncture in the twenty-first century. Most of us have been exiled from all that we've produced, reproduced, created, dreamed of, cared for, and loved -- our sense of being at home in our own world -- reduced to pressing our noses against the glass houses of the few who've stolen nearly everything from us and yet cruelly flaunt their abundance (a situation that's captured, even if poorly, in the 1% language of Occupy). We, the vast "pile of debris," can only look forward to austerity, which daily gets more austere.

I'm one of the relatively lucky ones in this present-day exilic existence, since it's more parts existential than, say, geographic or material, although at times -- like this past week, when I experienced a minor health issue -- it viscerally hits me how much most of us are increasingly being forced outside the human community in terms of basic needs like health care. For too many, the necessity-impossibility paradox has already heaped "wreckage upon wreckage" on them for decades or even centuries.

Like the Algonquins of Barriere Lake, five hours north of Montreal, who are presently trying to fend off Resolute Forest Products, which began active clear-cut logging of the Algonquins' traditional territories last week, and the riot squad, sent in by the government to enforce the logging (there's a solidarity casseroles at 11:30 a.m. on Wednesday, July 18 at 111 rue Duke, Montreal, http://www.facebook.com/events/413763868670087/). Like a family from Ville St-Laurent that due to racial profiling and the criminalization of immigrants, faces the deportation of the father this August, after thirty years in Canada, to a country he hasn't seen since he was nine, separating him from his partner, mother, and kids for years and perhaps forever (Solidarity across Borders is holding a "Beat the Borders" reggae music fund-raiser at 8:00 p.m. on Thursday, July 19 at 2009 Decarie, #108, Montreal, http://www.facebook.com/events/267149120057721/).

So many peoples, so many names, over so many catastrophes. Like in the now-tourist-attraction Pinkas Synagogue in Prague, where between 1954 and 1959, two painters took it on themselves to inscribe the names of 77,297 Bohemian and Moravian Jews murdered in the Holocaust on the walls of the main nave and adjoining areas. They included each person's birth and death dates, but in most cases, a deportation date to a concentration camp was the last known moment of each individual's life, and all that the artists (or perhaps these angels of history, battling in vain to "awaken the dead" with their act of remembrance) could record.

It's hard indeed to feel at home in this world, because this world offers little comfort and shelter to most of humanity. I come from a country that, for instance, spends three to five times more per year on incarcerating someone than educating them. Where it's normal not to have health insurance (forget health care), and just a routine part of life in a big city to see lots of people sleeping on the streets. Where's it's someone's own fault if they go hungry, can't pay their bills, or lose a job, or get depressed because of this. All this is reason enough for exile, and reason, even more, to stay and resist with others. A necessity and impossibility, bound up in the recent paradox of the name "Occupy," signaling an awakening for some and a further erasure and pain for others.

So last week in Montreal, when I ran across another piece of street art by Harpy, "EXIL," I got to thinking a lot about home, history, and exile. Because like exile, Harpy's work unsettles, as all good street art should at this unsettling moment (http://www.facebook.com/pages/Harpy/249684105126331/). Maybe this bison, a stopped-in-its-track still image from the stop-action series of photographs taken by Eadweard Muybridge (1830-1904) as well as a shorthand symbol for the exile and extermination of indigenous peoples of the Americas, like Benjamin's angel of history, isn't running away from something -- a passive victim. Perhaps this bison in Harpy's "EXIL" also has its face turned toward the past, toward the wreckage piling higher and higher, even as the winds of "progress" propel it with "such violence." Or maybe it's racing full-steam ahead (http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/24/Muybridge_Buffalo_galloping.gif), propelling itself toward its own half-compulsory, half-self-imposed exile, from which to then linger, look backward in its own good time, and contemplate what it would mean to "make whole what has been smashed."

That's likely not what Harpy intended, and maybe Harpy didn't even intend for our bison friend to evoke images of the "tragedy of yesterday" that was the American West but rather exiles and genocides of many peoples, from many places, over many times. I can ask Harpy in person the next time I run into their alter ego on the streets of Montreal, of course, but good street art is, I think, less about what the artist wants you to think; that would make it street decoration or paid advertisement. It's about making you think. Putting you outside yourself, and perhaps into the exile of engaging with the impossibility and yet necessity of social transformation.

I'd heard rumor that Harpy had some new pieces related to the student strike, ready to grace various alleyways and crumbling urban walls. So when I heard another rumor that Harpy and their late-night fairy-helpers were out wheatpasting one night last week, I wasn't expecting to see "EXIL" the next day. And I wasn't expecting it to stick in my head, like a song heard in the background, on radio waves wafting out of an open apartment window on the heavy summer air. I couldn't stop humming it in my head, turning its rhythms -- of that bison, galloping, fleeing, racing, running, maybe scared or maybe proud, or both -- over in my mind to try to hear what it was saying to me.

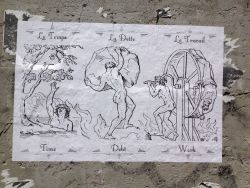

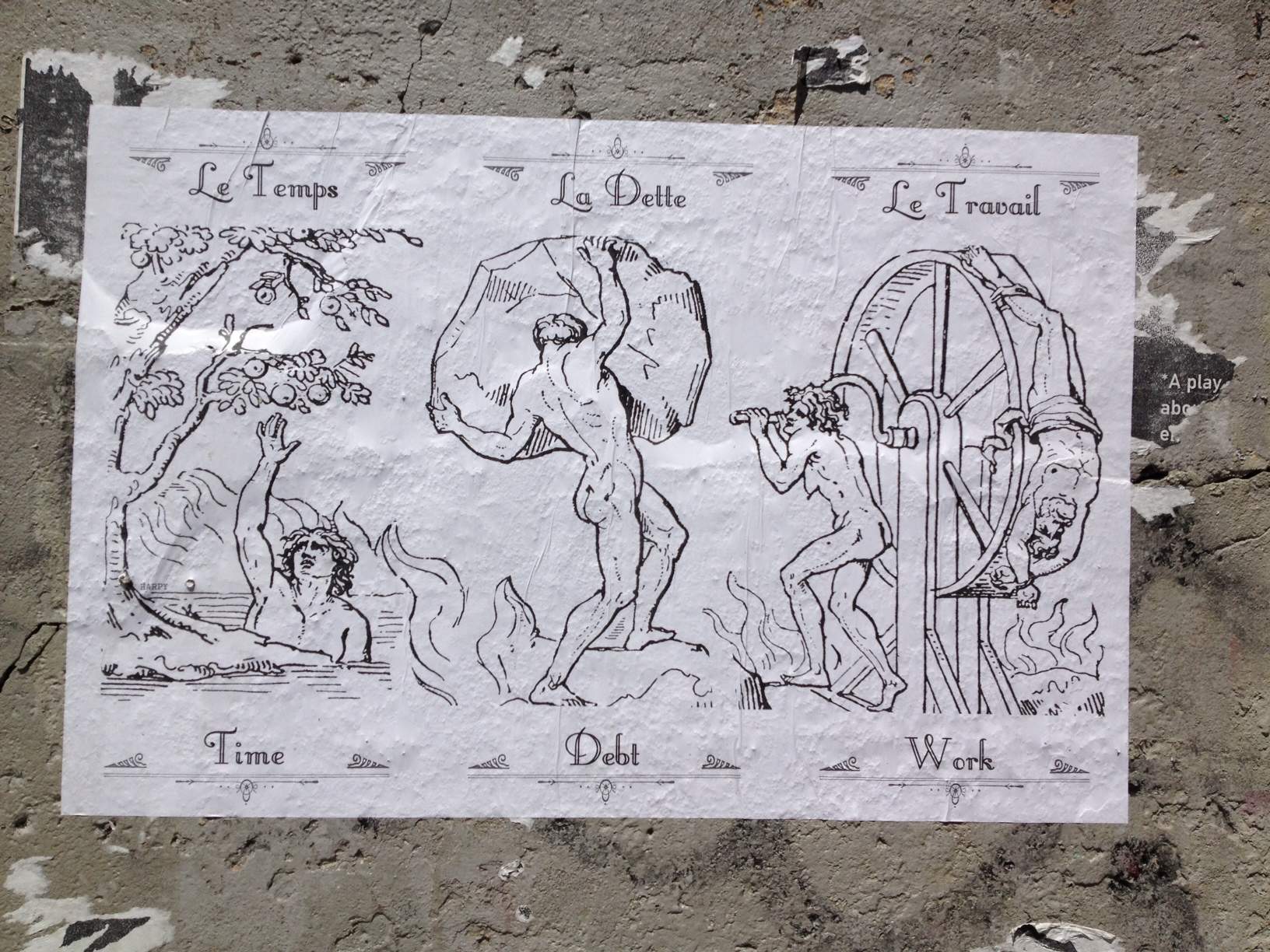

A few days later, I found another "EXIL" wheatpasted under a bridge, but this time it was in the same vicinity as another new Harpy piece, a triptych on austerity: "Time," "Debt," and "Work."

It was suddenly as if this bison was hurtling itself toward a new battle, even if it becomes it's last stand, against a capitalistic world seemingly hurtling itself toward its own self-annihilation, by destroying its own home -- its ecology, along with everything and everyone that inhabits it. "Austerity" is one more ugly means to exile vast swathes of humanity -- us -- by taking away all we need, and all we also desire, to be comfortably at home. Out of the impossibility of this moment, and certainly from necessity, people around the globe are (re)turning to experiments in what it might mean for us to take ourselves out of exile: from struggling toward the right of return to simply returning, from defending land to simply taking back the land, from fighting occupations to simply occupying those places that should be ours in common(s).

This is and probably will be no easy homecoming. The government does and will send in riot police, in greater numbers than the bison at their peak, to trample us. But maybe there's also no pristine home to come back to, either. We may be finding that we need to invent wholly new ways to house ourselves by first looking squarely at that "pile of debris," in which there's no comfy narrative of good guy versus bad guy, but only us fallible humans, most of whom are now suffering from the necessity and impossibility of being human in the face of austerity. The story of the bison's habitation and exile, life and death, stretches across many peoples and social structures, even if settler colonialism and commerce were the largest and final nails in its coffin. (Ah, I forgot, capitalism is breathing new life into the bison as niche-market commodity!)

I started this blog post thinking I was going to write about "The Form & Content of Social Goodness," which is probably just the flip side of the same coin I've been tossing around this evening, and what I'll turn to next. Because I've also been thinking a lot lately of the good society, the present, and making a home for ourselves in this world. Of reconstruction.

So I was struck today by the simple "social goodness" perpetrated by an anonymous crew of wheatpasters who seem to have done a second round of poetry posts to cover the corporate ads on the city rental "bixi" bikes. They proclaim that "BixiPoésie is the work of a group of . . . . students, workers, artists, activists . . . who dream of a world where art and culture flow freely in our streets. Where our minds are no longer stuck in the logic of might and economic reason. Where public space belongs to the citizens, rather than corporations" (http://bixipoesie.ca/). It is just one (albeit minor but telling) example of how the student and social strikers along with their allies are dreaming up strategies not to replicate the wreckage, which is kind of what Occupy feels like to me at the moment, or not to get "irresistibly propel[led] by "the storm" of the likely provincial elections "into the future to which [their] back is turned, while the pile of debris before [them] grows skyward." Instead, there is an effort here to "awaken the dead, and make whole" by focusing on a relation between means and ends, which is another way of asserting a relation between form and content, versus what seems to have become a lopsided fixation on form as content in Occupy, eviscerated of an ethics -- or social goodness. (Here's one example from Occupy, where both the "choices" offered by this author are just different versions of contentlessness as well as a lack of imagination, especially if one actually hopes to grapple with the wreckage of history and fly intentionally toward a better future; http://truth-out.org/news/item/10358-occupy-national-gathering-electrical-storms-and-insurrectionary-corpses.)

This isn't meant to romanticize Maple Summer. It's just to say that exile, chosen or not, unsettles one's perspective, and maybe there's something that can be gleaned from that -- to bring back home, if one has a home, or as the basis for even thinking about making home, or having the strength to attempt to do so.

The one thing I'm sure of tonight is, as imperfect angels on earth trying to make our own history in this inhospitable world, we're going to need strong wings indeed.

* * *

If you stumbled across this blog post as a reposting somewhere, please excuse the typos/grammatical errors (it’s a blog, after all), and note that you can find other blog-musings and more polished essays at Outside the Circle, cbmilstein.wordpress.com/. Share, enjoy, and repost–as long as it’s free, as in “free beer” and “freedom.”

(Photos of Klee's Angelus Novus and the resisting Algonquins of Barriere Lake borrowed from wiki and indie media sites; photos of Harpy's and BixiPoésie's work were taken by me, July 2012, Montreal)

About the poster

The site for the Montreal local of The Media Co-op has been archived and will no longer be updated. Please visit the main Media Co-op website to learn more about the organization.