When Enbridge shelved its Trailbreaker project due to the 2009 economic downturn, Quebecers heard right through the company’s talking points.

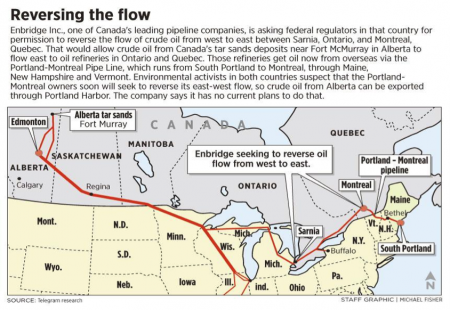

The Trailbreaker would have reversed the east-to-west flow of the existing Line 9 pipeline that links Sarnia, Ontario’s chemical valley, and Montreal in order to transport 240,000 barrels-per-day of Alberta tar sands oil to Montreal. The oil that wasn’t refined in Shell’s Montreal East refinery, now a distribution terminal, would have been exported to the Northeastern U.S. through the Portland-Montreal pipeline. Interestingly enough, although the reversal was shelved, Montreal Pipe Line Ltd. continued trying to build a pumping station in Dunham, Quebec, a key piece of the project’s infrastructure on the Quebec-Vermont border.

Sound familiar?

That’s because four years later, the Trailbreaker is back. The only difference: Enbridge has changed the name and broken up the project into smaller pieces. And although delegates from Calgary have visited Montreal to discuss exports to Europe and Asia, Enbridge claims the dirty oil flowing through Line 9A and Line 9B isn’t destined for export through the Montreal-Portland pipeline.

The nitty gritty regulatory process

On July 27 2012, the very same day that Enbridge spilled 1,200 barrels of oil in Wisconsin and two years after Enbridge spilled 20,000 barrels of tar sands crude into Michigan’s Kalamazoo river, the National Energy Board (NEB) approved the reversal of Line 9A, which runs from the Sarnia Terminal to the North Westover pumping station near Hamilton, Ontario.

In late November, Enbridge filed an application to reverse Line 9B, the 636 km of pipelines that run from North Westover to the Montreal Terminal – or, the remainder of the original Trailbreaker project. The company also requested an increase in the pipeline’s capacity to 300,000 barrels-per-day, and changes to regulations in order to allow the transportation of diluted bitumen (or ‘DilBit’), thick tar sands oil diluted with a toxic chemical cocktail that helps it scrape through pipelines like hot liquid sandpaper.

Pending NEB approval, Enbridge hopes construction will begin in late 2013 so the pipeline can be in service by Spring 2014. While the NEB will be holding public hearings regarding the reversal and capacity expansion, the Harper Government has the power to override decisions of the board. The majority government gave itself this power in its economic action plan, right after gutting a number of environmental regulations - upon the request of the oil and gas industry - in its 400+ page omnibus budget bill.

A bad deal for everyone and everything but Enbridge

Natural Resources Canada has budgeted over $9 million for ads promoting pipelines and resource development. Full-page ads in Montreal papers, funded by industry and commerce groups, say the reversal contributes to “sustainable development” in Quebec.

Joe Oliver says it’s just “good public relations.”

In reality, bringing tar sands oil out east is a bad deal for the climate, a bad deal for the economy, and a bad deal for the 99 municipalities, the 18 First Nation communities, and the 9 million people who live within 50km of the pipeline route.

Climate change is already affecting Quebecers. We wore t-shirts at the St. Patrick’s Day Parade; an early spring threatened our maple sugar season and apple crops; our streets flooded in Quebec City; and our cocktails warmed up on terraces even faster thanks to our sweltering July. Temperatures in March 2012 broke so many records that it broke the record for how many records were broken.

We need to leave 80% of the world’s fossil fuels in the ground if we want to avoid catastrophic climate change. Investing in infrastructure that locks us into further expanding tar sands production is just about the worst thing Canadians can do for the planet.

And unless everyone wants to move to Fort McMurray, Harper’s rhetoric that the tar sands create jobs and help the economy just isn’t true. Although the reversal project is expected to create a whopping three permanent jobs, more than 15 factory jobs have been lost for every natural resource employment position created since 2007 because of the stronger Canadian dollar. A pipeline in your backyard won’t really save you money at the pump, and getting oil of the ground has never been more expensive.

Pipelines carrying DilBit, like the one that spilled into the Kalamazoo River in 2010, are more likely to spill due to internal corrosion. The spills are also much harder to clean up, since the heavy bitumen sinks, while the chemicals evaporate into a toxic cloud that leaves nearby residents with headaches, nausea, and respiratory problems. Refining the tar sands crude would contribute even more to the horrible air quality in Sarnia and Montreal, and leave individuals with a higher risk of cancer.

Who wins? Nobody but Enbridge and the other corporations that are profiting off the privatization of the commons and the pollution of our planet.

Growing cross-border resistance

Pipelines have become one of the key political issues of the day, and thousands across North America are opposing these destructive projects. Last month, TransCanada rerouted the KeystoneXL pipeline after an 85-day tree-sit in Texas. Thousands are mobilizing across British Columbia to stop the Northern Gateway and Kinder Morgan pipelines and just this week, five people disrupted the Enbridge hearings in Vancouver to raise climate issues and condemn the process for silencing the voices of the public.

Quebec has stopped the Trailbreaker before.

Three years of organized civil resistance prevented the construction of the Dunham pumping station after the project received the go-ahead from Quebec’s Farmland Protection Commission in 2009. Two-thirds of residents signed a petition opposing the project, and many of the over 300 participants who attended a 2-week climate camp in 2010 pledged to take non-violent direct action if the pumping station was built without community consent. Citizens of Dunham also joined forces with Equiterre in order to win a number of successful court challenges against the pipeline company.

Now, Quebec is gearing up to stop the Trailbreaker once again, alongside neighbours in Ontario and the growing opposition across the U.S. border.

City councils in Burlington, Vermont and Casco, Maine have passed municipal resolutions opposing the transportation of tar sands oil through their cities and across their states. Burlington has also passed concrete measures to pull the city’s investments out of the tar sands and eliminate the city’s use of tar sands oil. Over 50 municipalities along the pipeline route in New England have similar resolutions on the table, and organizers in Toronto are building support around a motion that would prohibit shipping diluted bitumen through the city.

Perhaps Montreal Mayor Michael Applebaum’s attempts to clean up the city after Gérald Tremblay’s resignation will include measures that protect residents from the toxic impacts of a spill.

Looking ahead

This Saturday, Climate Justice Montreal is hosting a day of workshops, a panel, and collective strategizing to build resistance and alternatives to tar sands pipelines in Quebec. The event is the first in a week of cross-border actions in Ontario, Quebec, and New England, culminating in a massive demonstration in Portland, Maine on January 26th.

We know that there are two kinds of power, organized money and organized people. Dirty energy companies may have unlimited resources and the government’s PR machine at their disposal, but this weekend’s forum in Montreal is just the beginning of our collective resistance. We refuse to let one of the world’s richest oil companies turn Quebec into a dirty energy corridor.

This piece was originally published on Rabble.ca.