This piece is an expanded version of a text initially drafted for publication in two Montreal dailies.

The Gazette published a heavily-edited version of the op-ed that was submitted to them. The op-ed published in the Saturday, January 21, 2012 print edition of The Gazette (in english) can be read here.

Le Devoir published the op-ed that was submitted to them in its entirety. The op-ed published in the Saturday, January 14, 2012 print edition of Le Devoir (in french) can be read here.

***

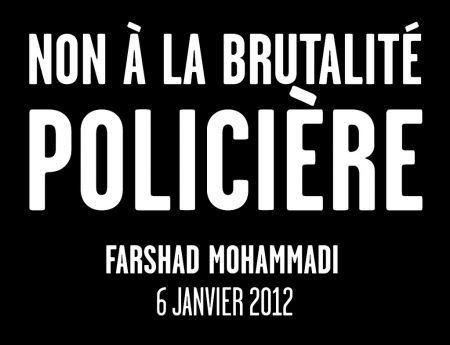

Farshad Mohammadi was killed on January 6, 2012, by a Montreal city police officer who shot him several times. There is very little known about the police intervention: it occurred in a busy metro station where Mohammadi was seeking shelter, a police officer was injured, and at least three gunshots were fired by the police.

Farshad Mohammadi’s killing has precipitated a flurry of calls to fund programs for homeless people and those with mental health issues. These calls have even come from opportunistic politicians like Montreal mayor Gerald Tremblay, highlighting the hypocrisy of the Tremblay administration’s professed concern about Mohammadi’s death given that it has gone to great lengths to avoid criticizing the deplorable use of police violence in Mohammadi’s killing.

Homeless people -- including those who are racialized (especially Indigenous people), use drugs and/or have mental health issues -- are disproportionately criminalized and incarcerated. The social and health services intended for them are drastically under-funded or simply non-existent right now, while funding paradoxically continues to be poured into expanding police forces and the prison system that criminalize them. However, while more funding may be necessary for social and health programs, it does not target the root causes of poverty and homelessness. Meanwhile, other systemic and institutional realities played a role in Mohammadi’s death, and must be explored if the goal is really to understand what happened and to prevent such deaths in the future.

Police profiling, violence and impunity

A primordial issue in Farshad Mohammadi’s killing is the social profiling carried out by Montreal city police. Police officers often harass people who are seeking shelter or sleeping in the metros, creating a climate of resentment and disdain vis-à-vis the police within marginalized communities. The circumstances in which Mohammadi allegedly injured a police officer before eventually being shot and killed remain unclear. But, according to eyewitnesses, Mohammadi wasn’t bothering anyone prior to the police intervention. So, the more fundamental question is why the police deemed it necessary to engage Mohammadi in the first place? Was he simply sleeping on the ground, as opposed to a bench? Had he been there for “too long”?

A second, and related, issue is that of police violence and impunity. Since 1987, it is believed that over 80 people have died at the hands of the Montreal police, including while in police custody. These deaths have also included the controversial killings of, among others: Anthony Griffin, Jean-Pierre Lizotte, Mohamed Anas Bennis, Quilem Registre, Fredy Villanueva and, this past summer, Mario Hamel and Patrick Limoges. Why was deadly force used in intervening with these individuals, many of whom were either racialized or homeless? In the province of Quebec, between January 1st, 1999 and June 30, 2011, there have been 339 investigations of police interventions that have resulted in serious injury or death. Criminal charges have been laid against officers only three times, with at least two of the trials resulting in acquittals! This impunity is largely explained by the fact that the province of Quebec still resorts to the archaic practice of calling on police forces to investigate each other in such cases. For example, the Sureté du Québec is conducting the investigation into Mohammadi’s shooting death and, if history is to serve as a guide, it is unlikely that we will ever really find out what happened, despite the fact that there were multiple eye-witnesses present and a multitude of video cameras that should have captured the incident. The end-result of all this is a culture of impunity that favors the use of force, including deadly force, whenever the police feel threatened.

Double punishment: targeting migrants

Precarious immigration status is a crucial systemic issue that contributes to the marginalization of migrants. Specifically, Farshad Mohammadi was the victim of “double punishment”, a draconian federal immigration policy, legislated via the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act, whereby permanent residents can be deemed “inadmissible”, stripped of their status and made deportable based on the nebulous qualification of “serious criminality”. Migrants without full Canadian citizenship end up facing a revolting situation: imprisonment followed by deportation, for the same crime. Poor and racialized migrants are particularly at risk, considering that both social and racial profiling have been widely documented in Montreal.

Mohammadi was a government-sponsored convention refugee from Iran who was granted permanent residency status here in Canada in 2006. In 2009, he was convicted of a break and entry offense of a non-residential building, for which he received a prison sentence of one day. In May 2011, Mohammadi was deemed “inadmissible” as a result of this conviction, despite having served his sentence. Purging a prison sentence is commonly regarded as “having paid one’s debt to society” for a criminal conviction. However, those without full Canadian citizenship not only “pay their debt”, they also lose their right to remain in the country legally! This demonstrates a cruel structural legal discrimination against accepted refugees and permanent residents. The nebulous and arbitrary nature of “serious criminality” is patent here: a non-violent crime with no victims fulfills criteria for Citizenship and Immigration Canada. In Mohammadi’s case, what adds insult to injury is that he may very well have broken into a non-residential building simply to be able to sleep somewhere!

Arash Banakar, the lawyer working on Farshad Mohammadi’s immigration case was confident that the deportation order would be overturned because of the recognition by Canadian immigration authorities that Mohammadi had been persecuted in Iran as a result of his Kurdish background and would be at risk of it again if he was deported, and because the crime he was convicted of did not involve violence against an individual and resulted in a minimal sentence. Despite these reassurances, according to Banakar, Mohammadi was in a “state of extreme panic” due to the threat of being deported back to Iran -- a state for which Canada’s immigration laws are responsible. We can only imagine Mohammadi’s state of mind at the time of the police intervention...

Capitalism, borders and policing: root causes of marginalization and injustice

The reality of homelessness, and the mental health issues that may accompany it, obviously played a role in Mohammadi’s death. However, it is unfair to imply, as some have, that homeless people are the problem because they are deemed to be threatening or violent by virtue of their homelessness. In fact, to our knowledge, no homeless person has been responsible for a single homicide in Montreal while, in the same time period (ie., from June 2011 to the time of this writing), Montreal police officers have killed two homeless people.

Homelessness is a problem, but it is not caused by homeless people themselves; it is caused by an economic system that allows for, and encourages, the asymmetric accumulation of wealth for some at the expense of the many through exploitation and oppression. Poverty becomes structural, not incidental: indeed, some people are rich because many others are poor. As such, the conditions that create homelessness and precipitate mental illness are allowed to reign. The consequences that follow should not come as a surprise to anyone.

In light of Farshad Mohammadi’s death, we cannot avoid the existence of gross injustices: poverty, homelessness, detentions and deportations, profiling and criminalization of marginalized communities, as well as police violence and impunity. All these must be opposed and brought to an end.

A media interview with someone who identified himself as one of Mohammadi’s close friends reported that Mohammadi was hoping to move to Ottawa to make a new life for himself there. Despite all the trials and tribulations he endured, Mohammadi still hoped for a better future. Perhaps the most scathing and tragic irony in Mohammadi’s case is that he fled Iran to avoid persecution and potentially death. Instead, he faced both here in Canada, a country that proclaims itself to be a just and free society. But just and free for whom? Certainly not for people like Farshad Mohammadi.

---

Anne-Marie Gallant is a member of the migrant-justice group Solidarity Across Borders. Over the last few years, she has been involved in various feminist initiatives and the student movement, all the while supporting struggles against police brutality. She works as a mental health nurse.

Robyn Maynard is a writer, community worker, and activist. She is involved in various campaigns against police violence and racial profiling, and is part of the No One Is Illegal campaign.

Samir Shaheen-Hussain is an anti-authoritarian and anti-capitalist organizer who has been involved in Indigenous solidarity, migrant justice, anti-police brutality and radical healthcare work over the years, and is part of the No One Is Illegal campaign. He works as a pediatrician in an emergency department.

A handful of other Montreal-based activists also contributed to the drafting of this text.