Victor Morales has lived in Montreal for 32 years, and is the father of three Canadian kids. Yet when the Chilean-born musician, who is the primary caregiver for his terminally ill Canadian mom, applied for permanent residence on humanitarian and compassionate grounds, Citizenship and Immigration Canada (CIC) rejected his application, citing petty crimes the Montrealer committed years ago. He now faces deportation to Chile, a country he has never once visited since he was six years old, when his family fled the terror of the Pinochet regime and were accepted as refugees to Canada.

When I spoke to Morales the weekend prior to his January 31 federal court hearing, he was beside himself. “It is as if they were sending a Quebecer who had never lived with those people over in Chile,” said the 40-year old Montrealer, in a telephone interview. “I’ve lived here my entire life,” added the musician, whose Andean songs are familiar to many riders of the Montreal metro (he busks regularly in the city's underground public transit system).

Canadian immigration authorities had originally scheduled his deportation for Tuesday, February 8. But last week, a federal court ruled to 'stay,' or delay Morales's deportation--a ruling that his lawyer attributed in part to Morales and his family's own vocal public opposition to the deportation order, which drew considerable media attention to the case.

For his lawyer, human rights attorney Stewart Istvanffy, the treatment the Montreal father received at the hands of Canadian immigration authorities is a disturbing indicator of a systemic problem that goes far beyond this individual case.

Quite simply, “our immigration system’s gone crazy,” Istvanffy warns.

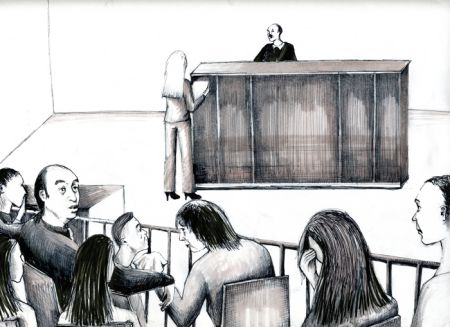

For those who crowded into the courtroom on Monday morning and listened to CIC's arguments rationalizing Morales's removal from Canada, it's hard to avoid this conclusion.

CIC's legal counsel, Sylvie Brochu, argued on Monday that Morales’s deportation order should be carried out without further ado because of the street musician’s alleged “great criminality.” Yet as judge Yves De Montigny observed in his decision to stay the Montrealer's deportation, Morales was not "someone who had committed serious criminal infractions." His offenses, which included possession of marijuana and petty theft, had in fact never been grave enough to warrant a single sentence of more than fourteen days. Moreover, he has not had any new convictions in more than six years.

What’s more, the punitive measure of deportation raises concerns about the specter of a discriminatory “double punishment” being inflicted on immigrants in Canada. Sarita Ahooja, a Montreal-based organizer with No One is Illegal-Montreal and Solidarity Across Borders, observes that "this case shows the double punishment imposed on non-citizens, who get deported for crimes already purged, with no regard to the fact that the penal system has already made them pay for their acts."

Moreover, Morales deportation would constitute an unfair punishment to the Montrealer’s whole family. In Tuesday’s federal court ruling, judge de Montigny pointed out, “Mr. Morales and his children will be seriously affected if they are separated for many years—or forever.”

To most people, this would seem an obvious point. Yet astonishingly, CIC told the court they lacked evidence that any “irreparable harm” would be caused by exiling the father of three Montreal kids to Chile.

With her back turned to the members of Mr. Morales’s family who packed the federal courtroom last Monday -- including his 13 and 14 year-old sons, his ailing 65-year old mom, his two young nieces and his brother-- Brochu argued that the government lacked proof of his ties with his family.

This despite the fact that Mr. Morales’s kids had submitted letters to CIC expressing what an important role their dad plays in their lives. Granted, he does not live with them, since his divorce from their mom. But as his two sons, and their mother, all testified in letters to the immigration authorities, he’s present on a daily basis in his children’s lives.

Moreover, Morales’s mother, who has AIDS, submitted testimony about the crucial role her son plays in her care, and Monica Morales’s doctor Sylvie Vezena testified that her patient’s health would likely deteriorate if it were not for the loving live-in primary care provided by her son.

Perplexingly, the immigration agent who rejected Morales’s application to stay in Canada on humanitarian and compassionate grounds stated that she gave “little weight” to his family's testimony, because it came from “interested parties” who were biased because they had a stake in the government’s decision over whether their kin was allowed to stay.

Before a courtroom packed with the sad, nervous and worried faces of these same “interested parties,” judge de Montigny expressed his bewilderment at CIC's reasoning.

“How is this a criteria for rejection?” he exclaimed during the hearing. If CIC gave “little weight” to testimony from Morales’s Canadian family in deciding whether Morales should be allowed to stay in Canada for humanitarian and compassionate considerations, what evidence would immigration agents consider?

In his ruling, the federal court judge diplomatically suggested that the immigration agent might have “erred in rejecting the letters testifying to the link that exists between Mr. Morales and his children,” who would “undeniably suffer great harm from the fact of” the absence of a parent to whom they were attached.

During the January 31 hearing, the CIC lawyer told the federal judge, “I know we break up families. But that’s our role.”

For many Canadians, it would likely come as news that breaking up families is part of the role of a taxpayer-funded Canadian government agency.

This disturbing function of Canada's deportation policies should concern us all, for as Istvanffy points out it represents “a clear violation of international law.”

CIC's legal counsel Sylvie Brochu declined to comment for this article.

A version of this article was published by Rabble.ca on February 7.