“On a besoin de faire un ménage,” says Bernard St-Jacques of the homelessness problem in Montreal, which amounts to 25,000 to 30,000 people according to the Réseau d’aide aux personnes seules et itinérantes de Montréal (RAPSIM).

St-Jacques is the community organizer for public space and jurisdiction at RAPSIM and the author of a report on social profiling released last Wednesday. Profilage social et jurisdiction: portrait de la situation dans l’espace public montréalais contains the results of a questionnaire asking 40 Montreal organizations about their experiences—and those of the homeless people who use their services—with social profiling.

The report was inspired by a similar one done by the Commission des droits de la personne et des droits de la jeunesse in 2009. Its most significant finding: homeless people receive a disproportiate number of fines from the police. The majority of fines were for minor infractions regarding “incivilities.” According to the report, Montreal’s homeless represent one per cent of the population but they were the subject of 31.6 per cent of the police reports in 2004, 20.3 per cent in 2005. The report concluded social profiling contributed significantly to these statistics, and made a series of recommendations to the Service de police de la ville de Montréal (SPVM).

Two years later, RAPSIM’s report commends the police on a few improvements in this area. SPVM documented a 30 per cent decrease in the number of fines given to homeless people between 2008 and 2009. It also partnered with the Équipe mobile de référence et d’interventions en itinérance whose members go on patrol with police, providing advice on approaching the homeless and suggesting alternatives to fines or arrest. “Ils (SPVM) ont changé de directives: au niveau des actions, on incite moins les patrouilleurs à s’attaquer aux personnes itinérantes,” says St-Jacques.

Still, 85 per cent of the respondents to RAPSIM’s questionnaire described the relations between homeless people and police as negative: 56 per cent reported being the victims of physical abuse and 46 percent reported verbal abuse or discrimination. Sixty-one per cent indicated they still frequently receive fines.

The report denounces police for rarely following procedure when it comes to situations involving homeless people. St-Jacques says nothing has been done since the release of the Commission’s recommendations to correct or reprimand this misconduct. Clinique droits devant, RAPSIM’s legal aid service, dealt with 16 cases last year concerning police misconduct, and sixty-three per cent of respondents described their legal situation as poor.

“L’attitude des policiers envers des personnes itinérantes n’a pas vraiment changé pour bon temps; la mentalité n’a pas vraiment changé,” says Johanne Galipeau of Action Autonomie, a mental health advocacy and legal aid organization that participated in RAPSIM’s questionnaire. “Peut être moins de contraventions, mais on manque de respect. Abus, brutalité: ces situations-là ne sont pas changées—peu changées.”

She criticizes police for being quick to use a heavy hand on a person acting outside “les normes de la société.” As a result, the homeless have made a connection between the police and being escorted to the hospital or prison, she says. Losing confidence in the “system” means the homeless have ceased asking for help.

Galipeau says police tend to receive the brunt of social profiling accusations because they are the first responders. But RAPSIM’s report indicates 60 per cent of respondents felt the treatment of homeless people in public spaces in general has improved little or not at all in the past five years—whether that treatment be from residents, business owners, other citizens or police.

“Police members are not apart from society,” says Marie-Eve Sylvestre. “They’re part of it and their construction or their perception of homelessness and of some people who may have characteristics of homeless people are also constructed by society.”

Sylvestre is a civil law professor at the University of Ottawa and was one of two researchers involved in developing RAPSIM’s report. She says social profiling by police stems largely from society’s narratives of homeless people. For instance, the misconception that all homeless are dangerous is often used as a justification for their arrest. “We believe the police have constructed a perception of the harm caused by homeless people based on the needs and complaints of very few individuals who have some power in the neighborhoods (where the arrests and fines are occurring),” says Sylvestre.

These complaints are possible, she adds, because some municipal bylaws and provincial laws concerning the use of public space discriminate against homeless people. Prohibitions against public drinking, public noise, public gathering and public drunkenness target the homeless in particular. These laws apply to all citizens, but people living on the street are more likely to violate them because they have no private address. “Le fait de ne pas avoir (des) espace privés, que ton espace privé devient finalement l’espace public, mais ça empêche une protection de tes droits,” says St-Jacques.

Between 2000 and 2003, more and more public places were being redefined as “parks” or “squares” meaning the city had more control over them, explains RAPSIM’s report. It became illegal to use public installations, like park benches or low walls, in a manner for which they were not intended (re: sleeping) and remain in public areas after their “closing times.” Céline Bellot, a researcher in the Centre international de criminologie comparée at the Université de Montréal who worked on RAPSIM’s report, documented a four-fold increase in the fines given out to homeless between 1994 and 2003.

St-Jacques also points to the development during this period of downtown Montreal’s infrastructure, housing, commercial areas, tourist attractions and festival spaces as a contributor to police’s targeting of the homeless population. Downtown organizations recorded worse relations with the police during the summer and festival seasons. “C’est évident,” St-Jacques says, “que la population marginalisée se trouvent dans le chemin de ces projets-là.”

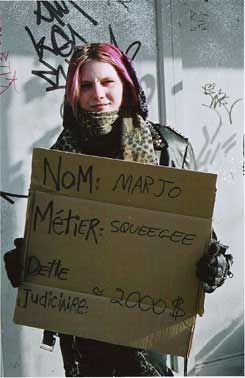

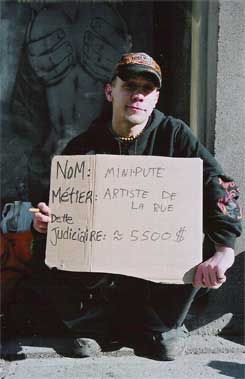

The inclusion of homeless people in these projects—and their reinsertion into society as a whole—could greatly deter social profiling, believes Richard Chrétien, director of Sac à Dos. His organization has strived to maintain positive relationships with the police officers, residents and business owners surrounding Sac à Dos’ Ste-Catherine/René-Lévesque location. Its members have worked in the community in urban development and cleanup projects, as well as with local stores and events like the Festival de Jazz and Francopholies. “Ça aide à parler un peu différamment des gens de la rue; pas juste voir les gens de la rue comme une problème, mais (de) voir la force des gens de la rue dans l’intégration,” Chrétien says before adding: “Puis, ça s’attaque au problème.”

The problem of homelessness, he means. Central to both RAPSIM’s and the Commission’s reports was the idea that homelessness is a societal failure leading to the denial of basics right to a part of its population. Both groups recommended a steep increase in services for the homeless and improved preventions to homelessness on the municipal and provincial levels.

In 2010, Mayor Gérald Tremblay announced the Plan d’action interministériel en itinérance. Despite the plan’s acknowledgement of a social profiling problem, St-Jacques finds it insufficient for its lack of proposed changes to discriminatory municipal laws and police training in regards to the treatment of homeless people. He is most critical of the minimal funding provided to programs and community groups working to improve the basic living conditions of the homeless: “On est loin de nos demandes, puis c’est en trop le cas au niveau de ce qui touche la jurisdiction et le profilage sociale.”

RAPSIM plans to continue its research in the area of social profiling. It will be teaming up with other organizations and the Commission des droits de la personne et des droits de la jeunesse to create a farther-reaching monitoring system that will include a demographic breakdown of social profiling trends, and statistics specific to Montreal’s various neighborhoods. St-Jacques wants to develop a better method of documenting cases of police abuse and misconduct. He hopes the Commission will align this work with its portfolio on racial profiling to form a stronger attack on this issue.